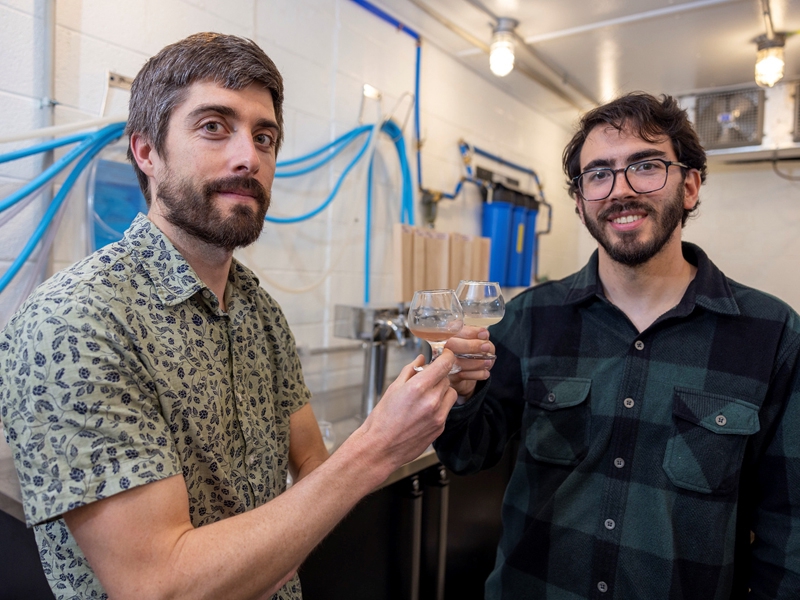

UofA rice malt researchers Scott Lafontaine (left) and Bernardo Guimaraes

UofA rice malt researchers Scott Lafontaine (left) and Bernardo Guimaraes

Apr 05, 2024

ARLINGTON, VA – Traditionally, beer is made with four simple ingredients: water, hops, yeast, and barley—a grain that, once it has germinated (or malted), provides the fermentable sugars necessary for the brewing process. Brewers can be purists about these four foundational components; Germany famously even codified them into law, stipulating that beer must be made with malted barley or it cannot legally be sold as beer.

But scientifically, barley is not the only grain that malts, and it’s not the only option when it comes to the raw materials required for brewing beer.

Barley, like rice, is a grass. The two grains share a number of physical and chemical characteristics, and rice has long been used to brew all kinds of beer—from Budweiser to small-batch craft microbrews. American brewers have been using rice since the 1860s to give their products a clean, crisp, refreshing taste, but rice is typically an adjunct step in that process, used in addition to barley and not as the main source of malted grain. Due to recent market developments, however, rice has the potential to play a much larger role in the beer industry.

Worldwide, higher-than-average temperatures and drought conditions have negatively affected both yield and quality of barley crops. Climate change coupled with global logistical and shipping issues means that barley is more expensive, harder to obtain, and varying in quality—all factors that are leading brewers to look to rice as an alternative.

A recent study from the University of Arkansas (UofA), authored by food science graduate student Bernardo P. Guimaraes, investigated the suitability of various U.S.-grown rice cultivars for malting. The team of researchers selected 19 rice varieties and tested their performance in the malting process, comparing them against brewing industry standards for evaluating raw material.

Of these original samples, 10 were selected for brewing trials, and nine of the malts they produced in the lab had enough enzymatic capacity to fully convert the grain’s starch into fermentable sugar—in other words, these U.S. rice varieties showed great brewing potential.

Scott Lafontaine, a flavor chemist and assistant professor of food science at UofA who advised Guimaraes’s research, thinks rice is overlooked as a starch source in brewing.

“It’s considered secondary, and I don’t understand why that’s the case,” said Lafontaine. “If I was a brewer, why would I import barley from another country when I’ve got a starch source right in my backyard that lets me create a beautiful product? At the end of the day, beer is made from malted grain. It doesn’t specifically need to be barley.”

The benefits of using rice malt to brew beer are severalfold: rice seems to be more resilient to climate change than barley and offers a more stable and local alternative for brewers facing global environmental and logistical challenges. Locally sourced rice could lead to more sustainable beer and shield U.S. brewers from market fluctuations, especially those based in rice-growing areas.

Lafontaine makes it clear that the intentions of this study are not to replace barley in beermaking, but rather to investigate the potential of rice malt as an alternative source of local starch for the many American brewers negatively impacted by barley prices and availability.

“The goal is to create another tool in the arsenal,” said Lafontaine. “A lot of mom-and-pop brewers, who make up a majority of breweries in the U.S., are buying barley on the stock market. Over the past three years, barley prices have increased by fifty percent. That kind of cost increase on a crucial raw material is crushing some of these small businesses. So it’s not necessarily a replacement, but an alternative. Climate change is going to put pressure on a lot of industries, and we need to be ready.”

The UofA study involved only small, lab-scale trials, as the main intent of the project was to determine the viability of different rice varieties in the malting step. But for Lafontaine and his team, the work continues: they’re currently running lab-scale brewing trials with the rice malt, producing beer that they can actually taste test.

“Bernardo brewed 10 different beers in the lab with the varieties that performed the best. Now we’re evaluating the sensory profiles of those products. Some taste a little funky, but some are performing well and yielding novel, pleasant flavor notes, like vanilla, coconut, and puffed rice cereal.”

The effort has been multi-institutional, involving materials and samples from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Louisiana State University, and UofA rice breeders, as well as analysis by a lab based out of Berlin, Germany, where Lafontaine previously worked as part of a fellowship. The research team is also working with an economist to determine the practical feasibility of brewing beer with rice malt.

“We have to prove that economically this makes sense, because without the economic picture there, I’m hesitant to say that this is a solution just yet. But from a scientific perspective, I think we’re pretty close to attaining the malting performance of barley.”